Parts of this story are reconstructed from trial testimony, evidence and publicly available records. It contains strong language throughout.

Four vehicles fly down a darkened, rain-soaked street. It’s summertime, nearly midnight in downtown Baltimore.

The lead car, a white Chevrolet, is driven by a 34-year-old man, his foot pressed to the pedal. On his tail are three unmarked police cars driven by members of the Gun Trace Task Force, a plainclothes gun recovery unit.

The chase started after the Chevrolet ran a red light. Pursuing the vehicle would be a violation of Baltimore Police Department policy, but the detectives suspect the man in the Chevy has guns, drugs, cash or all three.

“Might be able to get somethin’ dirty,” detective Daniel Hersl says excitedly.

“Light him up,” detective Jemell Rayam responds.

The pursuit proceeds to the sounds of revving engines and heavy rain pelting the windows - there are no sirens.

The Chevrolet blows through another red light. He almost makes it across the intersection when a Hyundai Sonata going through the green collides with the driver’s side of the Chevy, launching both cars up on to the pavement. The Chevy crumples into a motionless wreck.

“Shit!” exclaims detective Momodu Gondo from behind the wheel. “Damn.”

“Keep going,” responds his partner, Rayam. “I don’t know.”

“Shit!”

“I don’t know,” repeats Rayam. “I don’t know.”

Without stopping, the detectives radio back and forth between their cars.

“We ain’t look too crazy, did we?” asks Gondo. “They got cameras all up and down that shit.”

“I can get on the air and say I just got a report of an accident,” says Rayam.

“No, Wayne said - I wouldn’t say nothin’ yet,” responds Hersl.

Several blocks away, two of the three police vehicles pull to the side of the road and the officers confer. Gondo thinks he only had his lights on at the very beginning of the chase - maybe no one noticed them.

“That’s the thing with Wayne. He’s a little too much with this shit,” says Hersl. “These car chases. This what happens.”

Eventually it strikes the officers that they never called for aid.

“How about we just go on scene and just act like, ‘Oh, is everything OK?’” asks Rayam.

“That dude unconscious, he ain’t sayin’ shit,” responds detective Marcus Taylor.

Over half an hour after the crash,

they’ve still done nothing. Hersl suggests they change their time cards

to make it appear they stopped work hours earlier. Wayne Jenkins, the

unit’s leader, stops to scope out the accident, but also does nothing to

help.

“I wonder what was in that car,” says Hersl.

“I don’t care,” Jenkins snaps. “Go back to HQ.”

A year and a half later, in a federal courthouse in downtown Baltimore, a prosecutor switches off the audio recording from that night, captured on a FBI listening device hidden in Gondo’s police vehicle. On the witness stand sits Rayam, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a smooth pate. Instead of his police uniform, he wears bright orange prison garb.

Facing him from the defendants’ table are two of his former colleagues, Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor.

“None of us stopped to render aid or see if anyone was hurt,” Rayam tells the courtroom in a faltering voice. “We were foolish, I don’t know, we just didn’t… we just didn’t stop.”

In the case of United States versus Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor, the car accident is the least of the men’s legal worries. They are facing multiple counts of extortion, racketeering and fraud for their part in what prosecutors call a “perfect storm” of police officers gone rogue. Rayam, Gondo, Jenkins, as well as two other officers from the Gun Trace Task Force have already pleaded guilty.

When the prosecutor finishes his questions, Rayam seems to completely fall apart. He shields his eyes from the jury.

In an already exceptionally dramatic trial, it is a disorientating moment. As Rayam - a once-respected police detective, a college-educated father with a nice house in the suburbs - sobs silently on the witness stand, it is impossible not to wonder...

What happened to these police officers?

And something had always bothered

McDougall about the way the men operated, the openness of the drug

dealing he had witnessed after weeks of surveillance. He likened it to a

“fog” around the investigation.

And something had always bothered

McDougall about the way the men operated, the openness of the drug

dealing he had witnessed after weeks of surveillance. He likened it to a

“fog” around the investigation.

“It’s right out in front of us and nothing's being done,” he recalls. “I'm like, ‘There's something wrong here.’”

Anderson finally emerged from the room a little after 11am. As he and his girlfriend walked towards the Jeep, McDougall and his men surrounded them.

With the pair in handcuffs, McDougall radioed to a second team positioned outside Anderson’s apartment, and confirmed that it was safe to go inside.

As the secondary team searched the apartment, McDougall sat Anderson in the back of a squad car and asked what he was doing at the Red Roof motel in the first place.

“He’s like, ‘Two guys kicked in my door while my girl was home, stole stuff from me, they had handguns, I didn’t feel safe,’” recalls McDougall. “As he tells me that I get a phone call.”

It was the team at Anderson’s apartment - it was trashed. There was a boot print on the front door, the lock shattered. Drawers were pulled out of dressers. There were no drugs, just some digital scales and roughly 10 different mobile phones. Someone had beaten the officers there.

Anderson’s girlfriend told McDougall that two weeks earlier, a man with a hoodie pulled tight around his face ran into her bedroom, pointed a gun at her and threatened to kill her. He took jewellery, $10,000 in cash, a Rolex watch and a gun from their dresser. The second masked man headed for the kitchen. Anderson eventually revealed that 800g of heroin was stolen that day. Rather than call the police, the pair fled to the motel.

The same strange fog crept over McDougall. Something about the description of the way the apartment was tossed seemed oddly familiar.

The arrest team was wrapping up loose ends when one of the officers called out to McDougall. He was underneath Anderson’s Jeep, pulling off the magnetic GPS tracker McDougall had placed there weeks earlier.

“Hey Dave,” the detective said. “Do you have two on here? There’s another one.”

About eight inches away from McDougall’s GPS tracker was a second device. He was stunned.

McDougall knew for a fact no other law enforcement agency was investigating Anderson. In order to avoid stepping on one another’s toes, agencies enter the names and personal information of their investigative targets into what’s called a “deconfliction database”.

It’s a tool that allows local and federal agencies to see what investigations are already under way. McDougall had listed Anderson in deconfliction databases from “here to California” and nothing popped up.

“Right away it was kind of like, ‘Whoa, what's going on here?’” says McDougall. “Whose tracker is this?”

As soon as he returned to headquarters, McDougall wrote a subpoena for the company that manufactured the mystery tracker, asking them to identify the owner.

Within days he had a name: John Clewell. A driver’s licence photo showed a bald, moustached man in his 30s. When McDougall put the name into the Maryland court database to look for a criminal history, dozens of cases came up.

But it didn’t list Clewell as the defendant. Rather, it showed Clewell as a witness for the government. He was a cop. A detective with the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force.

McDougall formed a rough theory about what had happened - a Baltimore police officer, using the tracker, waited until Anderson’s vehicle was far away from his home, then used the opportunity to rob the apartment. The home invasion had some of the hallmarks of a police raid - the kicked-in door, the methodically tossed apartment. McDougall picked up the phone and called the FBI.

“I thought it was limited to maybe one or two guys,” he says. “That was going to be the end of the story.”

McDougall had no idea that what he had uncovered would lead to the arrest and indictment of eight police officers, nor that it would implicate at least a dozen more and point to a mole within the local prosecutor's office.

He had no inkling that it would unravel hundreds, and potentially thousands of criminal investigations, and free men from prison who’d sworn from the very beginning that they were framed, robbed, or both. It would one day explain the murder of a young father in front of his family, and raise endless questions about the death of a homicide detective, shot dead the day before he was supposed to testify against the rogue officers.

In the autumn of 2015, all of that was still to come.

“I wonder what was in that car,” says Hersl.

“I don’t care,” Jenkins snaps. “Go back to HQ.”

A year and a half later, in a federal courthouse in downtown Baltimore, a prosecutor switches off the audio recording from that night, captured on a FBI listening device hidden in Gondo’s police vehicle. On the witness stand sits Rayam, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a smooth pate. Instead of his police uniform, he wears bright orange prison garb.

Facing him from the defendants’ table are two of his former colleagues, Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor.

“None of us stopped to render aid or see if anyone was hurt,” Rayam tells the courtroom in a faltering voice. “We were foolish, I don’t know, we just didn’t… we just didn’t stop.”

In the case of United States versus Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor, the car accident is the least of the men’s legal worries. They are facing multiple counts of extortion, racketeering and fraud for their part in what prosecutors call a “perfect storm” of police officers gone rogue. Rayam, Gondo, Jenkins, as well as two other officers from the Gun Trace Task Force have already pleaded guilty.

When the prosecutor finishes his questions, Rayam seems to completely fall apart. He shields his eyes from the jury.

In an already exceptionally dramatic trial, it is a disorientating moment. As Rayam - a once-respected police detective, a college-educated father with a nice house in the suburbs - sobs silently on the witness stand, it is impossible not to wonder...

What happened to these police officers?

On the day of Aaron Anderson’s arrest,

Detective David McDougall of the Harford County Sheriff’s Department

rose around dawn and crept out of his house in rural Maryland before his

family awoke. He drove south to meet his team in the rear car park of a

Red Roof motel perched on a busy intersection in the suburbs of

Baltimore.

McDougall pulled on a tactical vest, preparing for just “another day at the office”. But nothing about the arrest of Anderson went as expected.

As a part of his work on the county’s narcotics task force, McDougall had been watching the 27-year-old suspected heroin dealer for weeks.

McDougall pulled on a tactical vest, preparing for just “another day at the office”. But nothing about the arrest of Anderson went as expected.

As a part of his work on the county’s narcotics task force, McDougall had been watching the 27-year-old suspected heroin dealer for weeks.

David McDougall

He’d sat outside Anderson’s drab

apartment complex in northwest Baltimore as he came and went. He'd also

placed a GPS tracking device on the undercarriage of Anderson's Jeep

Cherokee.

He’d observed surprisingly open drug sales at a strip mall, where Anderson was trailed by a small group of young men palming tiny plastic packets into the hands of drivers streaming in and out of the car park in full view of McDougall and his camera lens.

The very fact the arrest team was gathered at a motel that morning was the first surprise. Days earlier, they were ready to arrest Anderson at his apartment when he stopped going home. The GPS tracker on the Jeep was going to the Red Roof instead.

He’d observed surprisingly open drug sales at a strip mall, where Anderson was trailed by a small group of young men palming tiny plastic packets into the hands of drivers streaming in and out of the car park in full view of McDougall and his camera lens.

The very fact the arrest team was gathered at a motel that morning was the first surprise. Days earlier, they were ready to arrest Anderson at his apartment when he stopped going home. The GPS tracker on the Jeep was going to the Red Roof instead.

They snapped photos of Anderson and his

girlfriend as they stood on the balcony talking on their phones. When

it became clear the pair were not checking out anytime soon, McDougall

rewrote his warrants for the motel.

On the morning of 19 October 2015, he and his team sat in the car park waiting for the door to room 207 to crack open.

Anderson was the first in a series of dominoes McDougall hoped to topple. A major narcotics investigation concluded there were two Baltimore-based drug dealers supplying the bulk of the far more rural Harford County’s heroin: Anderson and a rival dealer named Antonio “Brill” Shropshire.

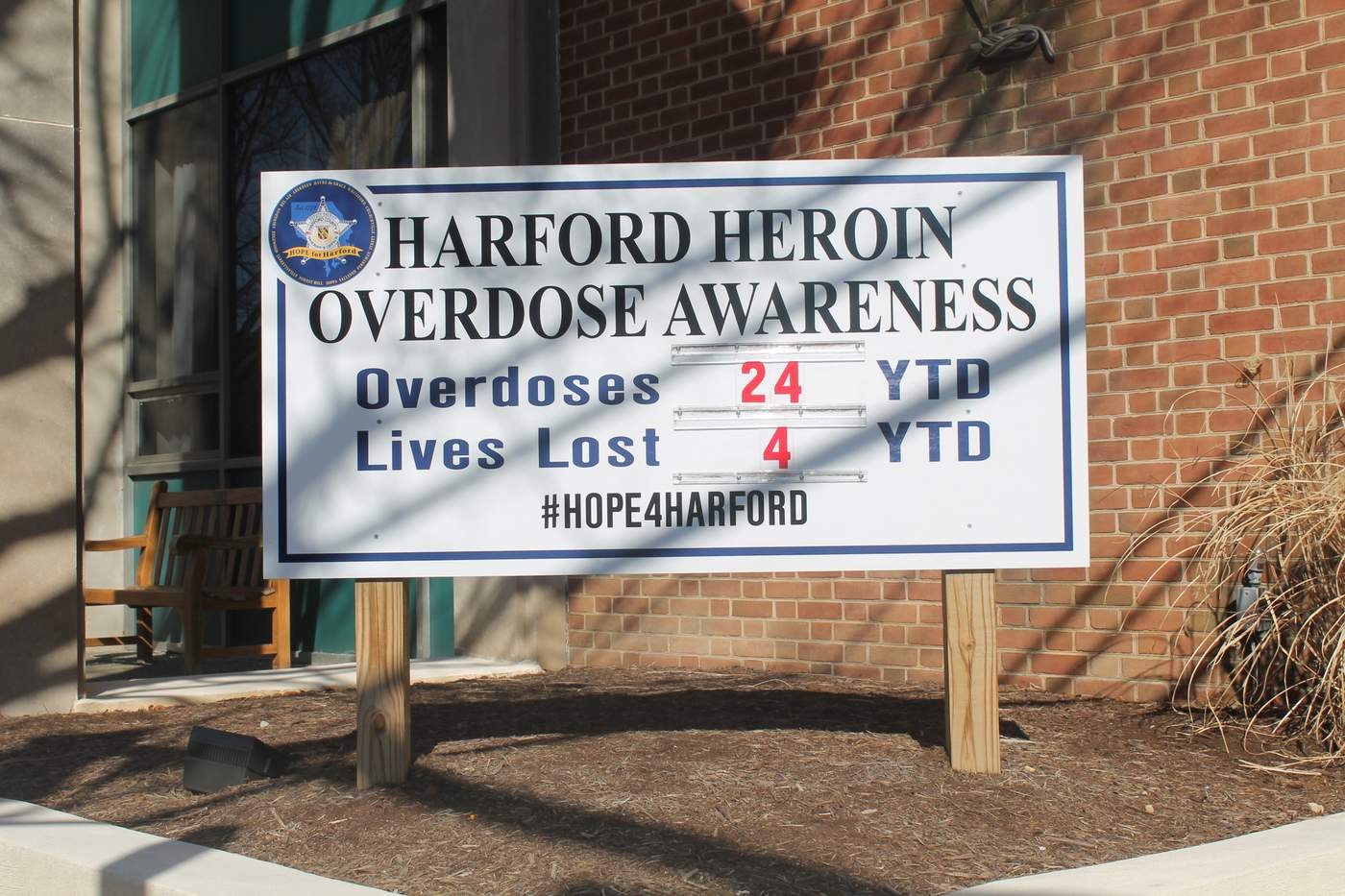

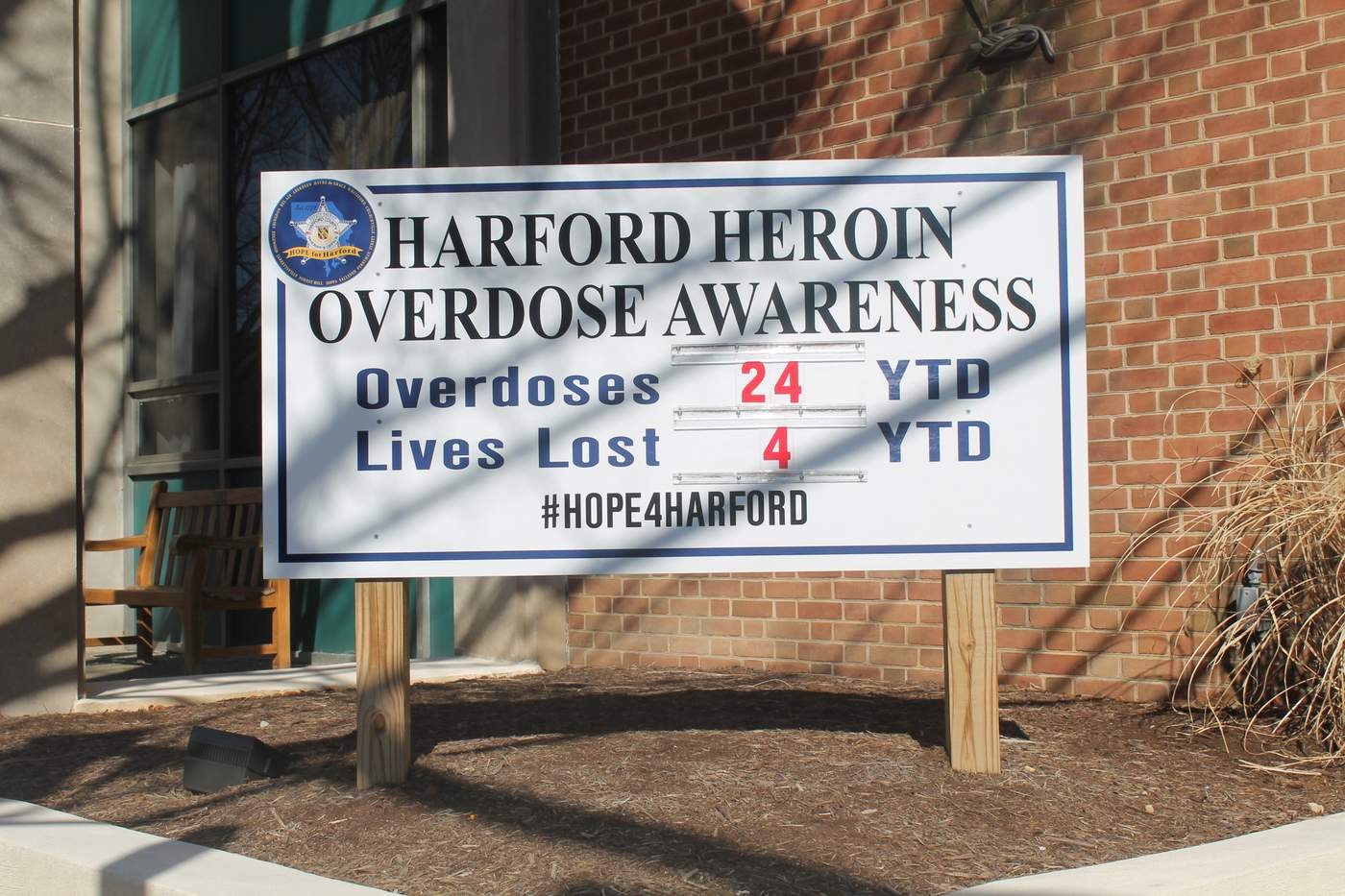

The two men had distinguished themselves in the eyes of law enforcement by peddling a particularly lethal product. In the last year, overdoses had skyrocketed in Harford County and McDougall believed as much as 80% were caused by heroin supplied by Anderson or Shropshire’s organisations. The deaths went as far back as 2011.

On the morning of 19 October 2015, he and his team sat in the car park waiting for the door to room 207 to crack open.

Anderson was the first in a series of dominoes McDougall hoped to topple. A major narcotics investigation concluded there were two Baltimore-based drug dealers supplying the bulk of the far more rural Harford County’s heroin: Anderson and a rival dealer named Antonio “Brill” Shropshire.

The two men had distinguished themselves in the eyes of law enforcement by peddling a particularly lethal product. In the last year, overdoses had skyrocketed in Harford County and McDougall believed as much as 80% were caused by heroin supplied by Anderson or Shropshire’s organisations. The deaths went as far back as 2011.

19-year-old Alyssa died of a heroin overdose in Harford County in 2011

“It’s right out in front of us and nothing's being done,” he recalls. “I'm like, ‘There's something wrong here.’”

Anderson finally emerged from the room a little after 11am. As he and his girlfriend walked towards the Jeep, McDougall and his men surrounded them.

With the pair in handcuffs, McDougall radioed to a second team positioned outside Anderson’s apartment, and confirmed that it was safe to go inside.

As the secondary team searched the apartment, McDougall sat Anderson in the back of a squad car and asked what he was doing at the Red Roof motel in the first place.

“He’s like, ‘Two guys kicked in my door while my girl was home, stole stuff from me, they had handguns, I didn’t feel safe,’” recalls McDougall. “As he tells me that I get a phone call.”

It was the team at Anderson’s apartment - it was trashed. There was a boot print on the front door, the lock shattered. Drawers were pulled out of dressers. There were no drugs, just some digital scales and roughly 10 different mobile phones. Someone had beaten the officers there.

Anderson’s girlfriend told McDougall that two weeks earlier, a man with a hoodie pulled tight around his face ran into her bedroom, pointed a gun at her and threatened to kill her. He took jewellery, $10,000 in cash, a Rolex watch and a gun from their dresser. The second masked man headed for the kitchen. Anderson eventually revealed that 800g of heroin was stolen that day. Rather than call the police, the pair fled to the motel.

The same strange fog crept over McDougall. Something about the description of the way the apartment was tossed seemed oddly familiar.

The arrest team was wrapping up loose ends when one of the officers called out to McDougall. He was underneath Anderson’s Jeep, pulling off the magnetic GPS tracker McDougall had placed there weeks earlier.

“Hey Dave,” the detective said. “Do you have two on here? There’s another one.”

About eight inches away from McDougall’s GPS tracker was a second device. He was stunned.

McDougall knew for a fact no other law enforcement agency was investigating Anderson. In order to avoid stepping on one another’s toes, agencies enter the names and personal information of their investigative targets into what’s called a “deconfliction database”.

It’s a tool that allows local and federal agencies to see what investigations are already under way. McDougall had listed Anderson in deconfliction databases from “here to California” and nothing popped up.

“Right away it was kind of like, ‘Whoa, what's going on here?’” says McDougall. “Whose tracker is this?”

As soon as he returned to headquarters, McDougall wrote a subpoena for the company that manufactured the mystery tracker, asking them to identify the owner.

Within days he had a name: John Clewell. A driver’s licence photo showed a bald, moustached man in his 30s. When McDougall put the name into the Maryland court database to look for a criminal history, dozens of cases came up.

But it didn’t list Clewell as the defendant. Rather, it showed Clewell as a witness for the government. He was a cop. A detective with the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force.

McDougall formed a rough theory about what had happened - a Baltimore police officer, using the tracker, waited until Anderson’s vehicle was far away from his home, then used the opportunity to rob the apartment. The home invasion had some of the hallmarks of a police raid - the kicked-in door, the methodically tossed apartment. McDougall picked up the phone and called the FBI.

“I thought it was limited to maybe one or two guys,” he says. “That was going to be the end of the story.”

McDougall had no idea that what he had uncovered would lead to the arrest and indictment of eight police officers, nor that it would implicate at least a dozen more and point to a mole within the local prosecutor's office.

He had no inkling that it would unravel hundreds, and potentially thousands of criminal investigations, and free men from prison who’d sworn from the very beginning that they were framed, robbed, or both. It would one day explain the murder of a young father in front of his family, and raise endless questions about the death of a homicide detective, shot dead the day before he was supposed to testify against the rogue officers.

In the autumn of 2015, all of that was still to come.

Here’s what the public was led to

believe about the Gun Trace Task Force, before the FBI arrested almost

every member of the squad:

That in a city still reeling from the civil unrest that followed the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in policy custody, the GTTF was a bright spot in a department under a dark cloud. The 25-year-old African-American man’s death after a ride in a police transport ignited a build up of decades of tension between Baltimore's black residents and the police, touching off days of demonstrations, including looting and violence.

That while the homicide rate was on a historic rise, this elite, eight-officer team was getting guns off the streets at an astonishing rate - their supervising lieutenant praised “a work ethic that is beyond reproach” that resulted in 110 arrests and 132 guns confiscated in a 10-month period.

That the GTTF’s leader, a former Marine and amateur MMA fighter named Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, was a hero who’d plunged into a violent crowd during the unrest to rescue injured officers, an act of bravery that earned him a departmental Bronze Star.

But when the sun came up on 1 March 2017, the city awoke to a vastly different reality.

Seven officers were arrested and indicted for racketeering, extortion and fraud: Sergeant Jenkins; Detective Daniel Hersl, a 17-year veteran of the force; longtime partners Detectives Momodu Gondo and Jemell Rayam; and Detectives Maurice Ward, Evodio Hendrix and Marcus Taylor. Only one member - oddly enough, John Clewell, the man whose name triggered the entire investigation - escaped indictment. The FBI found he was never a part of the criminal enterprise.

“They were involved in a pernicious conspiracy scheme that included abuse of power,” the US Attorney for Maryland told reporters that day. Police commissioner Kevin Davis, who’d once praised the men’s work, now likened them to 1930s-style gangsters.

“It’s disgusting,” he said.

That in a city still reeling from the civil unrest that followed the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in policy custody, the GTTF was a bright spot in a department under a dark cloud. The 25-year-old African-American man’s death after a ride in a police transport ignited a build up of decades of tension between Baltimore's black residents and the police, touching off days of demonstrations, including looting and violence.

That while the homicide rate was on a historic rise, this elite, eight-officer team was getting guns off the streets at an astonishing rate - their supervising lieutenant praised “a work ethic that is beyond reproach” that resulted in 110 arrests and 132 guns confiscated in a 10-month period.

That the GTTF’s leader, a former Marine and amateur MMA fighter named Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, was a hero who’d plunged into a violent crowd during the unrest to rescue injured officers, an act of bravery that earned him a departmental Bronze Star.

But when the sun came up on 1 March 2017, the city awoke to a vastly different reality.

Seven officers were arrested and indicted for racketeering, extortion and fraud: Sergeant Jenkins; Detective Daniel Hersl, a 17-year veteran of the force; longtime partners Detectives Momodu Gondo and Jemell Rayam; and Detectives Maurice Ward, Evodio Hendrix and Marcus Taylor. Only one member - oddly enough, John Clewell, the man whose name triggered the entire investigation - escaped indictment. The FBI found he was never a part of the criminal enterprise.

“They were involved in a pernicious conspiracy scheme that included abuse of power,” the US Attorney for Maryland told reporters that day. Police commissioner Kevin Davis, who’d once praised the men’s work, now likened them to 1930s-style gangsters.

“It’s disgusting,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment